Executive Summary

Status quo. The Turkish populace determined to stay the course when Prime Minister Erdogan was recently elected president of Turkey, extending his twelve-year rule via transference to a different executive post. While polls indicated that he was the leading candidate, and few doubted his capability to win, an analysis of his tenure as Prime Minister leads one to question why the Turkish populace would reelect such an authoritarian figure. He has failed to deliver on promises of expanding democracy, and has faced nationwide protest during the Gezi Park movement, which spanned multiple socioeconomic classes, ages and ethnic groups. Dissent was not isolated but rather a common grievance among the masses. Erdogan’s spotty record continued after protests were quelled, and in December 2013 his party was implicated in an international graft scandal, exposing the corruption surrounding Erdogan’s administration.

The former prime minister has made it no secret that he hopes to make the executive branch the overarching governmental arm, usurping judicial power through restricting the HYSK and releasing hundreds of police officers that did not cooperate with his attempts to cover up the graft scandal. Other undemocratic measures included placing the MIT (Turkey’s intelligence agency) under executive control and monitoring social media, such as banning Twitter. Despite these egregious violations of democracy and the public unrest against him, Erdogan won the presidential election, which presents an interesting puzzle. This paper seeks to answer why Erdogan was elected, and what domestic factors specifically contributed to his victory. Analysis will rely on a review of the positive impacts that Erdogan’s policies had, and how economic considerations played an integral part in keeping him in power. Despite his shortcomings, his executive overreach worked to bolster certain sectors of society through welfare programs and education expansion, and therefore overshadowed some of his authoritarian policies.

Erdogan’s Speckled Past

Democratic reformation. This was a campaign promise that seemed to have the potential to be actualized when Recep Erdogan was elected to the prime minister seat in 2002. The politician preached the tenets of freedom and incorporation of the periphery, running on domestic platforms such as the issues of human rights, liberties, constitutional reform and economic development. His campaign proposed constitutional reform to overturn the more authoritarian measures put in place by the military, but yet his rhetoric was never translated into action.

Legislation passed during Erdogan’s reign was highly controlling of the populace’s behavior and sought to impose certain ideals upon the Turkish public. Erdogan’s AKP party was transparent regarding their religious leanings in its campaigns, but was not clear about how it would use Islamic conservative values to control individual behavior. The legislation allowing headscarves to be worn in public- most notably in universities- actually gave religious sectors personal freedoms they had been denied, but conservative values ultimately led to some repressive tendencies. Among the restrictive measures put in place by Erdogan were restrictions on the sale, use and public projection of the image of alcohol, along with attempts to ban abortion.[1] He has continued the legacy of suppressing individualism and expression, indicating the need for reform. Disenfranchisement of many Turkish citizens became problematic as Erdogan interpreted democracy as “majoritarianism – rule by and for the majority, no matter how narrow, with little regard for consensus building.”[2] This adoption of majoritarinism dictated that following Erdogan’s election to office the opposition’s views had no legitimate place in policy formation.

This majoritarian stance directly led to widespread internal dissent, culminating in the Gezi Park Protest in May 2013, where nearly 3.5 million Turkish citizens took to the street to dispute their own government’s actions.[3] At the most basic level the demonstrations were in opposition to the proposals of the government to implement urban planning through restoring military barracks, in the process of developing a supermall in Gezi Park. Gezi Park served as a medium for individual expression, hosting small peaceful protests, cultural celebrations and art and music exhibitions. In a nation state that values conformity of identity, the park was a refuge for constructing the self outside government-enforced ideals. Generally considered a more polarized society, protests in Taksim Square of the wider Gezi Park created a unification of the core community which opposed the regime of Erdogan.

A survey conducted by the Bilgi University found that 91.1% of demonstrators strongly agreed that they were protesting for the protection of democratic rights, and only 7.7% were protesting against a specific political party.[4] This was not a short-lived political movement against one specific policy (Gezi Park’s destruction), but a demand for the government to reflect the middle class’s new conception of themselves and the security of their role as individuals. Citizens who came out in public were unhappy with the administration and were ready to force change.

President Erdogan’s response to the protests displayed the true heart of why citizens had gathered in the park. He applied brute force to those at Gezi, having the police arrest dissenters, beat them and use tear gas to deter the protestors from continuing.[5]This harsh response came along with his hardline rhetoric about demonstrators. He dismissed activists as a “few looters” and “a few bums.”[6] Later he was quoted by the media as saying, “this is a protest organized by extremist elements. We will not give away anything to those who live arm-in-arm with terrorism.”[7] The middle class protestors have attempted to create a new voice for Turkish citizens, but despite their position as a majority economic group, Erdogan demoted their cause to a periphery movement, isolating potential voters and supporters.

Erdogan’s legacy was scarred by the protests, with citizens losing faith in his ability to proactively lead a democratic country. He had proven through his unsympathetic and violent responses that he did not plan to address the democratic deficiency Turkey was experiencing, but rather cater to AKP supporters and the conservative religious groups. Lack of faith in Erdogan and his authoritarian tendencies were expounded when the corruption scandal sweeping the nation first came to a head on December 17, 2013 when over forty businessmen, government officials and their family members (mainly cabinet members’ sons) were detained by the Financial Crimes and Battle Against Criminal Incomes Department.[8] Those brought into custody were accused of a laundry list of crimes, including smuggling gold, money laundering and bribery. Economic corruption was not merely a domestic issue, but as evidence emerged, ties to Iran and al-Qaeda also became apparent.[9]

Erdogan has repeatedly violated the Turkish Constitution, specifically Article 28, which directly states not only that “the press is free, and shall not be censored,” but that “the state shall take the necessary measures to ensure freedom of the press and freedom of information.”[10] Erdogan has not fostered an environment of free media, but instead has actively facilitated the repression of this freedom, placing Turkey as the nation with the largest amount of journalists detained in prison worldwide. Freedom House’s 2014 “Freedom of the Press” report determined that Turkey was not free, demoting Turkey from its previous status of ‘Partly Free’. It is listed as number 62 on an international scale of freedom of the press, wherein 1 is the best and 100 is considered the worst.[11]

Evidence that Erdogan interferes with the media is overwhelming. His violations include placing pressure on journalists to only release pieces favorable to the administration, and punishing those who defect. Repercussions are severe for those journalists who do not bow to this pressure, and include detainment, unemployment and deportation if they are a foreign national. If the journalist is lucky enough to avoid detainment, they still are often threatened, harassed and attacked by the government. The Journalists Union of Turkey reports that in the Spring of 2014, ninety-four reporters were imprisoned in Turkish jails for criticizing governmental action.[12]

Erdogan has taken an active role in this repression. Several phone calls were released between AKP officials and media representatives, with one of the exchanges occurring with Erdogan and Mehmet Fatih Sarac, deputy chairman of Ciner Yayin. Among demands made were the removal of stories portraying the government pessimistically, changing headlines and removing text from reports about AKP opponents. With this leak emerging, Erdogan explained his behavior as protecting his image, since he was directly being insulted. He admits to making the call to have headlines under an opponent’s speech removed from Haberturk TV, but makes no apologies for his action.[13]

Information paths are also restricted by the government, behavior that is exemplified by the expulsion of journalists from police stations by Turkish authorities following the outbreak of the graft scandal. All reporters who had accreditation to cover police investigations had their credentials revoked along with their access to media briefing rooms. Reporters were forced to rely on invitations to government-controlled briefings where they could receive vetted information that had been approved by the executive for release. This invite-only approach allows the government to control information, specifically details surrounding the graft scandal that are acceptable to reach the public. Shielded from the severity of the corruption scandal, the population did not grasp how morally tainted their leader had become.

Erdogan also usurped the basic freedom of speech of his populace by banning key social media websites, such as Twitter. Prime Minister Erdogan’s government has slowly used the salami technique to erode democratic practices in Turkey- the Internet censorship bill, Law 6518- which gave the President of the Directorate of telecommunication (BIT), authority to control access to information on the Internet.[14] As the Internet has become popularized, attempts to control it have been in put in place prior to Law 6518. Most notable of Erdogan’s attempts to censor the Internet was with Law 5651 in 2007, which banned online insults to modern Turkey’s founder Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, as well as any sites that encouraged suicide, sexual abuse of children, the supply of illegal drugs, promotion of prostitution and unauthorized gambling. Despite the fact the law was targeted towards decreasing illegal activities, Erdogan broadened its scope, using it as a political tool. Since 2007, 37,000 websites have been denied operation by court orders. Among websites shut down were those deemed to be pro-Kurdish and pro-gay (including gay dating websites), along with any news networks considered to be associated with either group, further marginalizing the population.[15]

Why was he reelected?

Corruption, human rights violations, terrorist ties and minority disenfranchisement. These terms are often used to describe dictators who either usurped power through a coup or unfairly “won” elections. Although this is an adequate portrayal of now-President Erdogan, he has gained his seat through a free election, a fact that lends itself to the question as to why the populace would voluntarily place control of their country in the hands of someone with an autocratic nature.

Although the position has generally been a symbolic one lacking the same extensive powers that the Prime Minister holds, Erdogan will most likely prove to make the Presidential seat one of great influence. Traditionally powers delegated to the President are to return legislation to parliament, to appoint judges to the Constitutional Court and to act as the commander-in-chief of the army. Their other primary duty is to call meetings of parliament when they see fit.[16] This limited power had not appeared to fit Erdogan’s governance style, and as early back as November 2012, he has planned to change this uneven power distribution when he first proposed a constitutional amendment.[17] Awareness that Erdogan will indeed continue to be a resounding voice in the government makes the question even more pressing, regarding the eagerness of the populace to keep him in office.

The facts surrounding the elections are first important to establish in order to theorize about the populace’s decision-making process. Erdogan won 51.65 percent of the vote, with 20,670,826 votes out of a total of 40,019,352 votes. This percentage constitutes a majority, but not an overwhelming one, and because Erdogan only needed to receive over 50 percent to avoid a runoff round, the amount by which he won is negligible.[18] Erdogan did not overwhelmingly win, but the fact he only needed to get 50 percent of the vote plus one, allowed him to focus on sectors of the population that could be swayed to have faith in him, such as a more rural religious and conservative populace. As the below map indicates, the swatches of citizens living in the border areas (which have a high density of minority groups) tended not to support Erdogan, indicating a lack of equal distribution of support. Although this was not a landslide victory, the question still stands as to why nearly 52 percent of the voters checked the box next to Erdogan’s name.

Erdogan campaigned on the promise of creating a “New Turkey,” wherein he would promote democracy via normalization of politics in conjunction with improving social welfare and advancing the Turkish economy, by allowing it to become one of the top ten international economies. His slogans “Milli İrade, Milli Güç, Hedef 2023” (National Will, National Strength, Target 2023) and “Yeni Türkiye Yolunda Demokrasi, Refah, İtibar” (Democracy, Prosperity and Prestige on the Road to a New Turkey) promised a bright future for Turkey, and his campaign logo has been likened to U.S. President Barack Obama’s 2008 logo, wherein the idea of change prevailed.[20]

Erdogan created an air of hope around the prospect of him ascending to the position of president, although his track record should have made these types of promises seem outlandish and false. His achievements in over 11 years as Prime Minister are impressive and despite his shortcomings, there is reason to believe his promises[22]. Below I will examine how portions of these promises were echoed in his administration, and beneath his violations of human rights and democratic tenets, there was logical reasoning that he would be elected.

Since the AKP came to power in November 2002, economic growth has averaged 5%, inflation has been lowered and domestic reform has been dramatic, including in the healthcare, and education sectors.[23]

1. Economic Growth

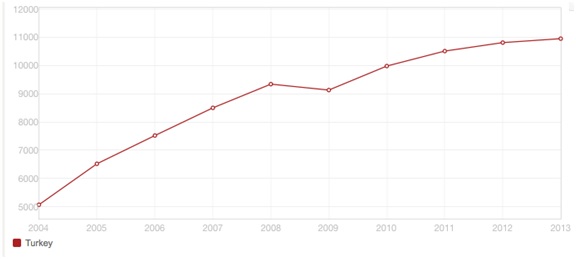

The gross national income of Turkey has continually risen in the last decade since Prime Minister Erdogan was elected in 2002. In 2003 the GNI of Turkey was approximately $4,000 USD, but by 2012 it had reached $10,830. Compared to other nations categorized as possessing Upper Middle Income, Turkey’s growth has been larger, with a difference of nearly four thousand dollars between Turkey and the average GNI of nations at the same income level.[24] Foreign direct investment dramatically rose from a miniscule $20 billion in 2001 to over $200 billion in 2014.[25] Unemployment rates dropped from 15 percent to 9 percent, lifting many Turkish citizens out of poverty. Fiscal prosperity reached a point where Erdogan was able to use revenues to pay off Turkey’s debt to the International Monetary Fund, wherein before his first term as Prime Minister, 90 percent of tax revenues were going simply to pay interest on this debt.[26] This was not just an economic success but a symbolic victory, as it ended a series of international humiliations that Turkey felt it suffered from in the past.[27]

Turkey’s GNI per capita, Atlas Method (current $US)[28]

The World Bank chart above shows the upward trend of the GNI growth from 2004 to 2013, wherein the GNI per capita more than doubled. The fact the GNI, which shows the amount of GDP growth in comparison to the population, is growing indicates that the general population was being uplifted. The growth of the middle class was corroborated by the following chart, which portrays how the money was being distributed throughout the general populace to bring them a higher standard of living. This distribution is important because a large portion of society experienced the economic growth, and therefore Erdogan’s constituents or potential supporters saw his reign as a success for them. The chart also projects that these groups will continue to grow leading up to 2020, and many would be led to believe that this could only be accomplished if Erdogan were still in power, since he was the initial spark for such economic growth.

Explanations for this rise are due in part to government-sponsored economic programs, such as the increase in trade with neighbors, most notably Iran. The government has embraced an open liberal order of international economy, rather than statist economic policy, and Turkey has benefited greatly from the market economy that Erdogan implemented. Although growth has slowed and economic experts are predicting this stagnation to continue, my analysis argues that it is not based on what Erdogan might do, but it is what he has proven to be capable of achieving.

The ripple effect of economic issues has not hit the Turkish population hard and therefore, they do not blame him for issues that will result in the future. Erdogan might not be a beacon of democracy yet he has created a strong Middle Eastern economy that is not based solely on the specialized export of oil, like its counterparts of Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Syria, and Kuwait. Money has been reinvested into the infrastructure of the country, modernizing the country as it gains economic prosperity. Transportation has drastically improved; the highway network has been expanded by 10,000 miles, and the number of airports rose from 26 to 50, with Istanbul’s third airport set to break ground.[30] Individual lives in conjunction with the country itself seem to be simultaneously improving. This economic success is what has given the population faith in Erdogan’s policies, and has significant explanatory power in suggesting why Erdogan won the election.

2. Social

Erdogan has helped shape Turkey into a fledgling welfare state, expanding state programs to create a security net for his people. He may not have reformed the government, but the AKP government has improved the educational system, social assistance system and healthcare system.

- Education

Before Erdogan became prime minister, education was severely underfunded, but he attempted to remedy the situation via increasing the yearly budget of the Ministry of Education from 7.5 billion lira to 34 billion lira.[31] This budgetary allocation is significant because education surpassed the military in receiving the highest net share of the national budget, indicating that education was truly a priority of the administration. The money was used directly on the students in a variety of programs, such as the F@tih Project, wherein state schools would receive a total of 620,000 smartboards. Additionally 17 million tablets were promised to Turkish students who also, beginning in 2004, had access to free textbooks.[32]

Access to education has also been widened, giving lower income students a better chance at increasing their chances of reaching a higher socioeconomic status. The University system has flourished under the AKP, wherein every province now has at least one university, and the number of those schools has risen by nearly 100 percent from 98 in 2002 to 186 at the close of 2012. Between 2002 and 2012 the number of students enrolled in university rose by 40 percent.[33] The public school system has been strengthened, expanding compulsory education from eight to twelve years via adopting a more Western-style structure. To ensure that all students ware getting the highest degree of education possible, the government also partnered with UNICEF in a “Come on Girls, let’s go to school campaign,” to close the gender gap in school enrollment, targeting the poorer sections of southeast Turkey.[34] College students who have access to education see the prospect for success, and parents of school ago children see the possibility of their children having a prosperous future.

- Welfare System

Domestically, Erdogan has made amazing strides, focusing his vision on the idea of a nation with a strong welfare system. His government has injected “liberalization, socialization and policy innovation” into its governance, which has yielded positive results,[35] swaying many to believe that what Erdogan provides for them physically outweighs his usurpation of power. Reforms achieved by him can be found in both social security and labor law.

Erdogan has also focused on family life, establishing the Ministry of Family and Social Affairs in 2011 to promote his pro-family agenda. This agenda has created a system wherein the family is the core part of the welfare system implemented in Turkey.[36]Under his tutelage, the rate of adoption has doubled and childcare facilities for the poor have increased 15 times itself.[37] Erdogan has added to his education policies to make a better future, or at least the perception of a better future, for the youth.

The Housing Development Administration has taken a more active role in bettering the shelter standards of Turkish inhabitants, and in the past ten years has constructed 565,000 public houses. Additionally the government has sought to prevent havoc wrought by natural disasters by strengthening 6.5 million houses against earthquakes in his Urban Transformation Program.[38]

III. Healthcare

Under the Health Transformation Program, healthcare has undergone effective reformation, which as its slogan states, puts “People First”. Among areas targeted are the improvement of the quality and efficiency of healthcare, with special emphasis placed on the restructuring of the Ministry of Health to give it a stronger hand in “development, planning, supervision of implementation, monitoring and evaluation.”[39] Additionally, it is now the primary healthcare provider for the nation.

Since 2010 the Family Medicine Programme has been established to ensure that all patients have a primary physician. Community health centers that provide free logistical support to family physicians have become commonplace and are the driving force behind important health pushes like vaccine and disease prevention campaigns. Successes of Erdogan’s efforts can be seen in the increase of the GDP spent on healthcare, rising from 5.4 % in 2002 to 6.1 % in 2008. The numbers reflect that the citizens themselves have felt the effect of Erdogan’s efforts, such as the rapid expansion of health insurance coverage, which grew from 69.7% in 2002 to 99.5 % in 2011. The percentage of out-of-pocket spending present in the total health expenditure decreased from 19.8 % in 2002 to 17.4 % in 2008. Dramatically, the percentage of people who had to pay for their medicine or therapy bills without the help of health insurance dropped from 32.1% in 2003 to only 11.1% of the population in 2011.[40] The health, and therefore the livelihoods, of the population have been improved, making Erdogan seem like a savior rather than a tyrant.

Conclusion

Erdogan may be like a dictator, but in terms of authoritarian figures, he would meet the bill of what Ronald Wintrobe describes as a tin-pot dictator, who uses benefits to gain loyalty from their subjects to maximize the time they are in power. Typically a tin-pot dictator combines loyalty through economic incentives with repression. This repression is characterized by a lack of freedom of expression and control of media output, and crushing dissent of the government.[41] Turkey’s media is not seen as free, and during the Gezi Park protests the world witnessed the willingness of Erdogan to stop those who opposed his policies, including the use of police brutality.

This lack of media freedom is essential in further explaining Erdogan’s election, because as prime minister he was able to utilize media sources to only portray positive pictures of his policies. In the OSCE report on election monitoring, the SCE/ODIHR “media monitoring results showed that three out of five monitored TV stations, including the public broadcaster, TRT1, displayed a significant bias towards the Prime Minister.” This was translated into a specific advantage as his speeches and rallies were broadcast live on television, whereas his opponents did not experience the same coverage. Media portrayals of the election were uneven, and in political advertisements Erdogan produced the highest proportion.[42] Pluralistic information was not disseminated to the public, nor were criticisms of Erdogan’s regime. They saw the good of what he achieved without being reminded of the past discretions of which he was guilty.

Similarly, Erdogan can be compared to what Olsen in “Dictatorship, Democracy and Development” would call a stationary bandit. This bandit is manipulative and corrupt but is still seen as a benevolent leader because of the economic performance that he produces. The bandit only takes a portion of the earnings of the citizens, and reinvests much of it back into society through projects such as infrastructure.[43] Erdogan has done this through his expansion of the transportation system, investment in education and healthcare reformation. Now more than ever the taxes established by the government are making their way back to the citizens so they can enjoy the fruits of their labor just as much as the government. Under these circumstances people tend to gravitate towards a peaceful organized society regardless of the posture of their leader. An autocrat who produces a better life may in fact be better than a democratic leader under whose rule the citizens suffer extensively.

Erdogan has been able to maneuver around the corruption scandal, and the aftermath of the Gezi Park protests, because he has created domestic wealth for his citizens. Economically the nation is flourishing, and by reinvesting the taxes back into the nation’s future, Erdogan has assured that not only the wealthy elite have benefited from the surplus of monetary gains. By providing education and social services, a wide net has been cast throughout Turkey to garner support for the AKP and people were able to overlook bad political acts because they are being provided for. One must look deeper than Erdogan’s spotted past and autocratic ways to understand the deeper sentiments of 52 percent of voters who are determined to keep him in office. By electing Erdogan President, they hope not to extend his power, but to extend the decade of personal gains that they have experienced.

Works Cited

A Turkey and Internet Censorship,” Organization for Security and Co-operation in

Europe.http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/pdf/speak_up/osce_freedom_of_the_media_on_turkey_and_iternet_censorship.pdf kdeniz, Dr. Yaman. “Report of the OSCE Representative on freedom of the Media on

Altinsoy, Selcen. “A Review of University facilities in Turkey,” OECD.

2011.http://www.oecd.org/edu/innovation-education/centreforeffectivelearningenvironmentscele/48358175.pdf

Bombey, Daniel. “How Erdogan did it- and could blow it,” The New Turkey. December

18, 2013.http://www.thenewturkey.org/how-erdogan-did-it-and-could-blow-it/new-economy/8597

Calatayud, Jose Miguel. “Just a few looters: Turkish PM Erdogan dismisses protests as

thousands occupy Istanbul’s Taksim Square,” Independent. June 2, 2013. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/just-a-few-looters-turkish-pm-erdogan-dismisses-protests-as-thousands-occupy-istanbuls-taksim-square-8641336.html

“Can Recep Tayyip Erdogan revitalize Turkey’s economic fortunes?” CNN, August 29,

2014. http://edition.cnn.com/2014/08/29/business/mme-turkish-economy-

erdogan/

“CUMHURBAŞKANI,” NTV. 2014. http://secim.ntv.com.tr

De Bellaigue, Christopher. “Turkey: Surreal Menacing…Pompous,” New York Review of

Books. December 19, 2013.

“Erdogan on top,” The Economist. August 16, 2014.

http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21612154-it-would-be-better-turkey-if-presidency-remained-mainly-ceremonial-erdogan-top

Esen, Bunyamin. “Myths and Facts about Turkey’s Welfare Regime,” The Daily Sabah.

August 26, 2014. http://www.dailysabah.com/opinion/2014/08/26/myths-and-facts-about-turkeys-welfare-regime

Esen, Bunyamin. “Social Welfare Context of Erdogan’s Presidential Vision: Turkey

Towards a Welfare Society?” The Daily Sabbah. August 2, 2014.

“Freedom of the Press 2014,” Freedom House. 2014.

http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/2014/turkey#.VBNmgty5Mds

García-Herrero, Alicia, Alvaro Vidal-Abarca, David Turegano, and Diana Posada-

Restrepo. “Emerging middle class in “fast-track” mode,” Economic Watch. 2013.

“GNI per capita, Atlas Method (current US$),” The World Bank. 2014.

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD/countries/TR?display=graph

Gole, Nilufer “Gezi – Anatomy of a Public Square Movement,” Insight Turkey. 15, no. 3,

2013.

Gursel, Kadri. “Erdogan’s heavy hand in Turkish media,” Al-Monitor. February 9, 2014.

Harkinson, Josh. “The Protests in Turkey, Explained,” Mother Jones. June 3, 2013.

http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2013/06/instanbul-erdogan-turkey-protests-explained

“İşte tutuklu gazetecilerin isim isim listesi,” Gazeteciler Online. February 7, 2012.

http://www.gazetecileronline.com/newsdetails/4770-/GazetecilerOnline/iste-tutuklu-gazetecilerin-isim-isim-listesi

Logothetis, Georgia. “The 5 worst quotes from Prime Minister Erdogan about the Turkish

protests,” Hellenic American Leadership Council. June 3, 2014.

http://hellenicleaders.com/blog/the-5-worst-quotes-from-prime-minister-erdogan-about-the-turkish-protests/#.UmbcilOcvoY

Olson, Mancur. “Dictatorship, Democracy, and development,” American Political

Science Review. Vol. 87, No. 3. September 1993.

“Press freedom advocacy groups slam Erdogan for targeting journalists,” Today’s Zaman.

June 4, 2014. http://www.todayszaman.com/news-349521-press-freedom-advocacy-groups-slam-erdogan-for-targeting-journalists.html

Rahmanpanah, Ghazal. “Crisis in Turkey: A case of Endemic corruption,” Monterey

Institute. May 2, 2014. http://sites.miis.edu/miisfinancialcrime/2014/05/02/crisis-in-turkey/

Seibert, Thomas. “Turkish PM Erdogan hit by allegations of son’s meeting with “oAl

Qaeda financier,” The National. Janaury 6, 2014 .http://www.thenational.ae/world/europe/turkish-pm-erdogan-hit-by-allegations-of-sons-meeting-with-0al-qaeda-financier

Soner, Cagaptay. “The Middle Class Strikes Back.” The New York Times. August 01,

2011.

“Statement of Preliminary Findings: Republic of Turkey- Presidential Election, 10

August 2014,” OSCE. http://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/turkey/122553?download=true 4.

“Turkey: Country Cooperation Strategy at a glance: World Health Organization,” World

Health Organization. May 2013. http://www.who.int/countryfocus/cooperation_strategy/ccsbrief_tur_en.pdf

“Turkey’s Erdogan is inaugurated as president,” BBC. August 28, 2014.

“Turkey’s new law on Internet curbs draws concern from UN rights office,” The United

Nations. February 14, 2014. http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=47143#.VBZKR9y5Mds

“Turkish Prime Minister’s Campaign Logo Looks Like Obama’s,” View Times. July 7,

2014. http://www.viewstimes.com/turkish-prime-ministers-campaign-logo-looks-like-obamas-535

Uras, Umut. “Erdogan promises a “new Turkey,” Al Jazeera. July 12, 2014.

http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2014/07/erdogan-promises-new-turkey-20147127316609347.html

Vela, Justin. “Erdogan’s Presidential ambitions,” Al Jazeera. August 27, 2013.

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2013/08/201382795036739875.html

Wintrobe, Ronald. “The Tinpot and the Totalitarian: An Economic Theory of

Dictatorship,” American Political Science Review. Vol 84. 1990.

“Yuksek Secim Kurulundan Duyuru, YSK. August 10, 2014.

http://www.ysk.gov.tr/ysk/content/conn/YSKUCM/path/Contribution%20Folders/HaberDosya/2014CB-Kesin-416_a_Yurtici.pdf

[1] Nilufer Gole, “Gezi – Anatomy of a Public Square Movement,” Insight Turkey, 15, no. 3 (2013): 7-14.

[2] Cagaptay Soner. “The Middle Class Strikes Back.” The New York Times, August 01, 2011.

[3] Christopher de Bellaigue, “Turkey: Surreal Menacing…Pompous,” New York Review of Books, December 19, 2013.

[4] Josh Harkinson, “The Protests in Turkey, Explained,” Mother Jones, June 3, 2013. http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2013/06/instanbul-erdogan-turkey-protests-explained

[5] “Press freedom advocacy groups slam Erdogan for targeting journalists,” Today’s Zaman, June 4, 2014. http://www.todayszaman.com/news-349521-press-freedom-advocacy-groups-slam-erdogan-for-targeting-journalists.html

[6] Jose Miguel Calatayud, “Just a few looters: Turkish PM Erdogan dismisses protsts as thousands occupy Istanbul’s Taksim Square,”Independent, June 2, 2013. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/just-a-few-looters-turkish-pm-erdogan-dismisses-protests-as-thousands-occupy-istanbuls-taksim-square-8641336.html

[7] Georgia Logothetis, “The 5 worst quotes from Prime Minister Erdogan about the Turkish protests,” Hellenic American Leadership Council, June 3, 2014. http://hellenicleaders.com/blog/the-5-worst-quotes-from-prime-minister-erdogan-about-the-turkish-protests/#.UmbcilOcvoY

[8] Ghazal Rahmanpanah, “Crisis in Turkey: A case of Endemic corruption,” Monterey Institute, May 2, 2014. http://sites.miis.edu/miisfinancialcrime/2014/05/02/crisis-in-turkey/

[9] Thomas Seibert, “Turkish PM Erdogan hit by allegations of son’s meeting with “oAl Qaeda financier,” The National, Janaury 6, 2014 .http://www.thenational.ae/world/europe/turkish-pm-erdogan-hit-by-allegations-of-sons-meeting-with-0al-qaeda-financier

[10] Article 28, Turkish Constitution, http://global.tbmm.gov.tr/docs/constitution_en.pdf

[11] “Freedom of the Press 2014,” Freedom House, 2014. http://www.freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-press/2014/turkey#.VBNmgty5Mds

[12] “İşte tutuklu gazetecilerin isim isim listesi,” Gazeteciler Online, February 7, 2012. http://www.gazetecileronline.com/newsdetails/4770-/GazetecilerOnline/iste-tutuklu-gazetecilerin-isim-isim-listesi

[13] Kadri Gursel, “Erdogan’s heavy hand in Turkish media,” Al-Monitor, February 9, 2014.

[14] “Turkey’s new law on Internet curbs draws concern from UN rights office,” The United Nation, February 14, 2014. http://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=47143#.VBZKR9y5Mds

[15] Dr. Yaman Akdeniz, “Report of the OSCE Representative on freedom of the Media on Turkey and Internet Censorship,” Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe. http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/pdf/speak_up/osce_freedom_of_the_media_on_turkey_and_iternet_censorship.pdf

[16] Constitution of Turkey.

[17] Justin Vela, “Erdogan’s Presidential ambitions,” Al Jazeera, August 27, 2013. http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2013/08/201382795036739875.html

[18]“Yuksek Secim Kurulundan Duyuru, YSK, August 10, 2014. http://www.ysk.gov.tr/ysk/content/conn/YSKUCM/path/Contribution%20Folders/HaberDosya/2014CB-Kesin-416_a_Yurtici.pdf

[19] “CUMHURBAŞKANI,” NTV, 2014. http://secim.ntv.com.tr

[20] “Turkey’s Erdogan is inaugurated as president,” BBC, August 28, 2014.

[21] “Turkish Prime Minister’s Campaign Logo Looks Like Obama’s,” View Times, July 7, 2014. http://www.viewstimes.com/turkish-prime-ministers-campaign-logo-looks-like-obamas-535

[22] Umut Uras, “Erdogan promises a “new Turkey,” Al Jazeera, July 12, 2014. http://www.aljazeera.com/news/middleeast/2014/07/erdogan-promises-new-turkey-20147127316609347.html

[23] “Erdogan on top,” The Economist, August 16, 2014. http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21612154-it-would-be-better-turkey-if-presidency-remained-mainly-ceremonial-erdogan-top

[24] The World Bank, “GNI per capita, Atlas method (current US$) .”

[25] “Can Recep Tayyip Erdogan revitalize Turkey’s economic fortunes?” CNN, August 29, 2014. http://edition.cnn.com/2014/08/29/business/mme-turkish-economy-erdogan/

[26] Daniel Bombey, “How Erdogan did it- and could blow it,” The New Turkey, December 18, 2013.http://www.thenewturkey.org/how-erdogan-did-it-and-could-blow-it/new-economy/8597

[27] Ibid.

[28] “GNI per capita, Atlas Method (current US$),” The World Bank.http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD/countries/TR?display=graph

[29] Alicia García-Herrero, Alvaro Vidal-Abarca, David Turegano, and Diana Posada-Restrepo, “Emerging middle class in “fast-track” mode,” Economic Watch (2013): 2.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Bunyamin Esen, “Social Welfare Context of Erdogan’s Presidential Vision: Turkey Towards a Welfare Society?” The Daily Sabbah,Augusst 2, 2014.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Selcen Altinsoy, “A Review of University facilities in Turkey,” OECD, 2011.http://www.oecd.org/edu/innovation-education/centreforeffectivelearningenvironmentscele/48358175.pdf

[34] Esen, “Social Welfare Context of Erdogan’s Presidential Vision: Turkey Towards a Welfare Society?”

[35] Bunyamin Esen, “Myths and Facts about Turkey’s Welfare Regime,” The Daily Sabah, August 26, 2014. http://www.dailysabah.com/opinion/2014/08/26/myths-and-facts-about-turkeys-welfare-regime

[36] Esen, “Social Welfare Context of Erdogan’s Presidential Vision: Turkey Towards a Welfare Society?”

[37] Esen, “Social Welfare Context of Erdogan’s Presidential Vision: Turkey Towards a Welfare Society?”

[38] Esen, “Social Welfare Context of Erdogan’s Presidential Vision: Turkey Towards a Welfare Society?”

[39] Turkey: Country Cooperation Strategy at a glance,: World Health Organization, May 2013. http://www.who.int/countryfocus/cooperation_strategy/ccsbrief_tur_en.pdf

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ronald Wintrobe, “The Tinpot and the Tolitarian: An Economic Theory of Dictatorship,” American Political Science Review, Vol 84, (1990).

[42] “Statement of Preliminary Findings: Republic of Turkey- Presidential Election, 10 August 2014,” OSCE,http://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/turkey/122553?download=true 4.

[43] Mancur Olson, “Dictatorship, Democracy, and development,” American Political Science Review, Vol. 87, No. 3. (September 1993).

[SA1]Very informative and impartial paper on the state of Turkish politics and the AKP